How Knowledge Builds

.jpg)

When my daughter was a toddler, she saw an ambulance crossing a nearby bridge. She was mesmerized by its siren and flashing lights—and terrified by the idea that someone needed help so urgently. After long minutes of burying her face in my shoulder, she started asking questions about the ambulance. When the questions continued for days, we took a trip to the local library. A heroic children's librarian helped us find illustrated nonfiction books about ambulances and hospitals, along with a rhyming fantasy story of a dragon, princess, and knight who become traveling doctors.

Something remarkable happened as we read (and reread and reread and then read again!) the books. My daughter started using words I'd never before heard in her vocabulary. Not just ambulance and doctor, but healthy, sick, bandage, and medicine. Although the books covered different aspects of emergency medicine, some of the same ideas came up in all of them. These repeated experiences with new words and concepts helped her soak up new information.

Another striking change: Bedtime reading became much longer. Seemingly overnight, my daughter graduated from short, simple board books like Goodnight, Moon to longer books with detailed information about medical treatments. By reading many books on one high-interest topic, she built new knowledge that allowed her to understand more complex content. And she had fun doing it!

My children have gone through many phases of interest since then, from construction sites to Star Wars, but I notice the same pattern—they understand more and become more curious when they dive deeply into one topic than when they jump around. Any moment can inspire questions: watching an ambulance, hearing a song lyric with a puzzling reference, or finding an injured bird. That spark of curiosity sharpens children’s focus and drives them to learn more. As children build knowledge of a complex topic, they gain new insights and ask even better questions. It’s a cycle that reinforces itself.

This is knowledge building, and it works for toddlers, teens, and adults. Regardless of age, our brains are wired to make connections. As Natalie Wexler explains in The Knowledge Gap, “The more knowledge a child starts with, the more likely she is to acquire yet more knowledge. She’ll read more and understand and retain information better, because knowledge, like Velcro, sticks best to other related knowledge.”

What might knowledge building look like in different subject areas?

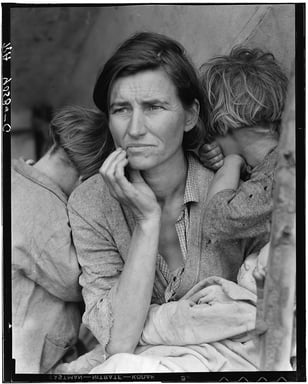

In English language arts, students can discuss and write about collections of texts related to one multifaceted topic. For example, students can build knowledge of resilience in the Great Depression by exploring the novel Bud Not Buddy, Langston Hughes’ poetry, and Dorothea Lange’s photos.

Students can build knowledge of resilience in the Great Depression through books, poetry, and photography.

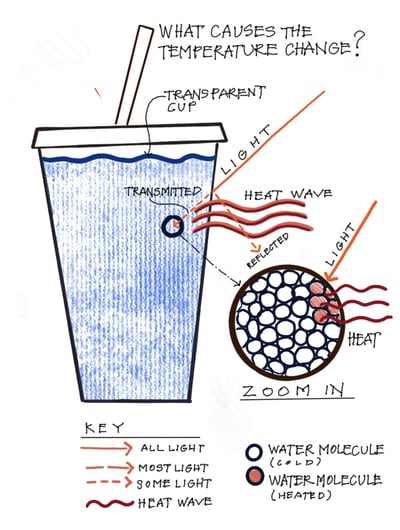

In science, students can explore a particular phenomenon—an observable natural event—and learn scientific concepts that help explain that phenomenon. Say students observe that some cups keep drinks cool longer than other cups. They can then investigate thermal energy to explain how that happens.

Students can draw diagrams to model how liquid in a cup changes temperature.

In history, students can look closely at different periods around the world, asking how events in one time and place influence others. For example, they might compare revolutions in the United States, France, and Latin America.

In math, students can connect new learning with familiar concepts to better understand big ideas over time. For example, young students start learning about fractions—often a difficult concept—by breaking familiar shapes and objects into pieces and describing them as parts of a whole. As students progress, they start comparing fractions, exploring questions like “Why is ½ of a birthday cake more than ⅓ of a birthday cake?” As students enter middle school, they deepen their knowledge by exploring even more abstract problems with fractions, such as “If one store sells 3 pencils for $1 and another store sells 7 pencils for $2, which option is cheaper?” When students gradually build knowledge of fractions, they come to understand that fractions work like any other number.

Every time a child builds knowledge in one area, they’re more likely to understand other subjects. Being open to knowledge is what allows it to build. Nothing amazes me more than watching knowledge grow in young minds—I see it with my own children as well as with students around the country.

In future posts, we'll explore how to build knowledge at home. Stay tuned.